A Brief History of LEAN

LEAN manufacturing originated at Toyota in the decades following World War II, where engineers developed what became known as the Toyota Production System. Facing limited resources, Toyota focused on eliminating waste, stabilizing processes, and designing systems for flow rather than scale.

By the 1980s and 1990s, these principles were studied, formalized, and adopted globally as LEAN, spreading far beyond automotive manufacturing.

Today, LEAN principles are widely used across industries including aerospace, electronics, medical devices, pharmaceuticals, consumer goods, energy, logistics, and healthcare, as well as in non-manufacturing fields such as software development and services.

Despite differences in products and regulation, the core LEAN objective remains the same across industries: deliver value reliably by designing systems that minimize waste and maximize flow.

What LEAN Really Means in Cell & Gene Therapy

LEAN starts with a deceptively simple idea: waste.

In LEAN thinking, waste is defined as anything that consumes time, resources, or effort without creating value for the patient.

Not everything that is necessary is value-adding, but everything that does not add value should be minimized, simplified, or removed.

In cell and gene therapy, waste rarely looks obvious. It shows up as:

- Batches waiting for QC release

- Operators waiting for equipment or approvals

- Critical equipment and clean room space idle

- Material moving across rooms and buildings

- Rework driven by variability

- Automation that increases steps instead of reducing them

LEAN does not ask whether these activities are sophisticated. It asks whether they move therapy closer to the patient.

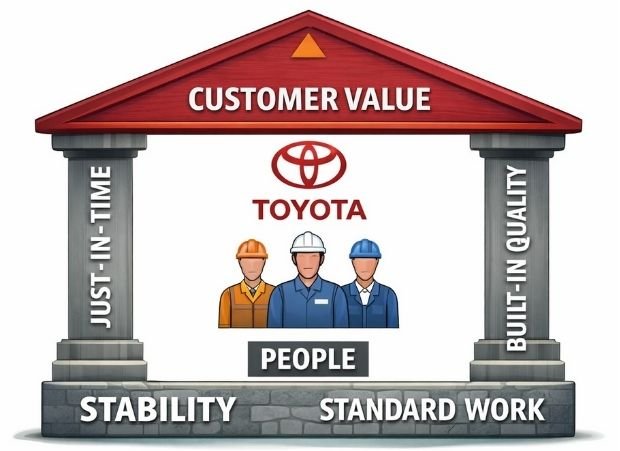

The House of Toyota: A Simple Framework (the structure behind the common sense)

LEAN is often explained through the House of Toyota, a visual model that shows how world-class manufacturing systems are built.

For beginners, think of it this way:

The Foundation: Stability and Standard Work

In LEAN’s original formulation, the foundation of the system was Heijunka, the leveling and sequencing of work to create a steady, predictable flow.

Heijunka is often misunderstood as a scheduling technique. In reality, it is a system design principle: work is intentionally leveled to remove peaks and valleys that destabilize people, equipment, and quality. In cell therapy manufacturing, this foundation translates directly into stability and standard work.

Stability is not an abstract goal. It is the precondition for Heijunka. Without repeatable processes, trained operators, controlled inputs, and clearly defined ways of working, work cannot be leveled, only reacted to.

-

The Pillars: Just-In-Time and Built-In Quality

Just-In-Time is about flow: making only what is needed, when it is needed, in the amount needed. Built-In Quality means problems are detected immediately, at the step where they occur, not weeks later in downstream testing. -

The Roof: Customer Value (Patient value)

In our industry, the customer is the patient. Value is not scientific elegance, it is timely, reliable access to therapy. The biggest waste of all is a life-saving science not reaching a patient in need. -

At the Center: People

LEAN systems depend on people who can see problems, solve them, and improve the process every day. Operators are not interchangeable labor; they are the system’s sensors..

Why This Matters for Cell Therapy

Cell therapy manufacturing struggles not because it is new science, but because systems are built around optimization of parts instead of flow of the whole.

LEAN shifts the question from: “How do we make this step better?” to “How do we make the entire therapy move faster, safer, and more predictably to the patient?”

LEAN is not about cutting corners. It is about removing friction, and in a field where time, cost, and reliability directly impact patient access, that distinction matters.

This is why LEAN is not optional for cell and gene therapy, It is foundational.